Quote, “The obvious is so commonplace that when waved in front of our noses we often don’t give it a moment’s thought or even realize it’s there. We take certain objects so for granted that we probably never stop to ask ourselves how they first figured in the life of man. This is the case with scissors: do they date back one century, two centuries or twenty? Our stainless steel kitchen scissors were probably bought from a market stall around the corner, but when did the first scissors come into the world? Attempting to track down the name of a crackpot inventor would certainly be of no avail; as in many similar cases, scissors were not invented in a flash of creative genius, but rather evolved, step by step, alongside many other tools destined to cut, separate and pierce, undergoing modifications of design, material and decoration from the first, primitive examples — or at least from the first examples revealed by archeology and literature — to the scissors of today.” - From Scissors by Massimiliano Mandel.

See below for a sampling of these evolving objects and further quotes from Mr Mandel’s beautiful (though it would seem, out of print) book.

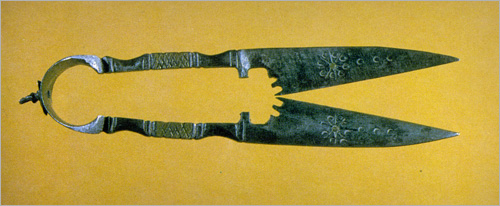

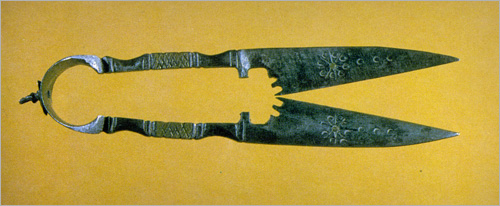

Iron scissors. Eastern Mediterranean, 14th Century.

2nd century A.D. Trabzon, northeastern Turkey.

Household Scissors. Italy, about 1550.

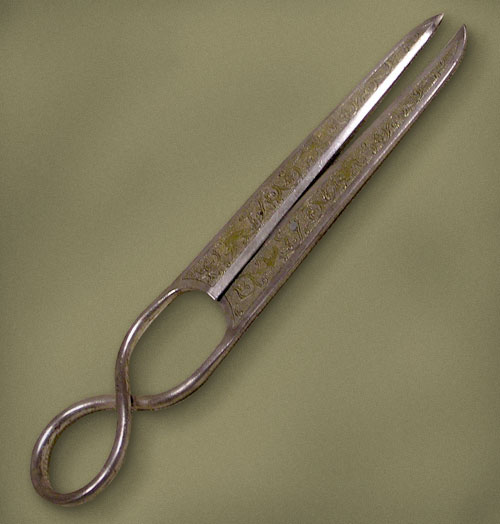

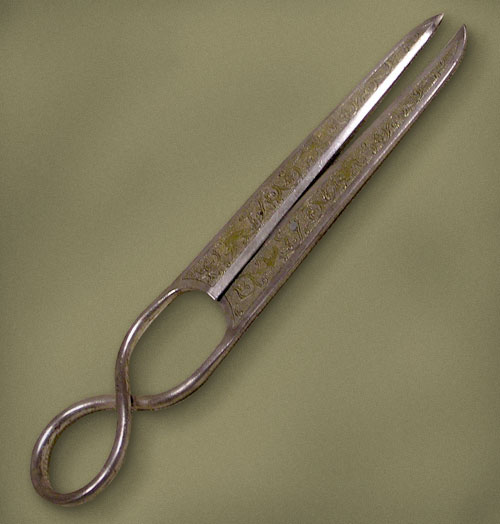

Persian Tailoring Scissors. 17th Century.

Tang Dynasty (618-907), 7th to 9th Century.

The first mention of (modern) scissors dates back to the Romanesque period, in the statutes of the craft guild for scissor-makers, one of the many associations of artisans founded in that period. The love of pure, unadorned construction that characterizes Romanesque architecture is reflected in the predilection for simple scissor design, with no decorative elements to distinguish them from previous examples. Only at the end of the Romanesque period, between the Xl and XII century, can one begin to notice greater attention being paid to the shape and quality of scissors, partly due to the development of relations with Eastern countries bordering the Mediterranean. Indeed, as the art of calligraphy spread throughout the Islamic world and scissors with concave blades used to cut sheets of paper became a necessary part of the calligrapher’s equipment, more refined models began to appear with thin, streamlined blades, engraved or damascened.

Candle-Trimmers. Italy, 16th Century.

Medieval Scissors.

Tinsmith’s Shears. Spain, 17th Century.

Viticulture Scissors. Italy, 19th Century.

Areca Nut Scissors. India, 18th Century.

If certain implements, such as knives and swords, axes and tongs, bear witness to the development of masculine taste and inventiveness while rarely attaining the status of works of art, scissors, on the contrary, are a more delicate testimony to the development of feminine taste and also to the attention paid to the style and sensitivity of the fairer sex by men. Indeed, a potential suitor sending a “love-box” to a lady of rank in the XIV century would be sure to include a pair of scissors in a leather sheath, an accessory of Muslim origin. It was in this century that scissors began to acquire their typically feminine connotations which, aside from certain examples specially designed for particularly demanding jobs, they have retained throughout their history.

Sugar-loaf Scissors. Brussels and Munich, 17th Century.

Shears / Detachable Blades. Italy, 1890.

Neoclassical era Italy or France, about 1820.

Decorated Steel Fretwork. England, 1875.

Calligrapher’s Scissors. Turkey, 18th Century.

Scissors gradually came to be appreciated for their aesthetic appeal, although the available space for decoration is slight compared to other hand-made objects, being difficult if not impossible to sculpt, emboss, embellish or paint. Rather, a black metallic alloy called niello was used to decorate the far end of the blades and a fretwork design was frequently applied around the rings of the handles. In this way a high degree of aesthetic pleasure was derived from these objects, which also enjoyed a relatively wide distribution. Unlike other objects such as arms, shields and so on, which once made into objects of art become too fragile for common use and are therefore only used as objects to put on display during parades and ceremonies, beautiful scissors also managed to be useful and so the taste for decoration became part of everyday life.

Shaped like a stork carrying a baby. England.

Embroidery Scissors. The Romantic Age, France.

Cigar Cutters. Italy, 1915.

Egg Scissors. France, 1930.

Unknown. Housed at the Fairfield Museum.

It would seem that from the industrial revolution onward scissors returned for the most part to their previous state, as purely functional items. Most traces of decoration have been absent ever since, in favor of a clean-lined, stainless-steel functionality.

Unfortunately scissors seem to be one of those items for which there is very little said on the internet from an historical standpoint. Massimiliano Mandel’s book book then is a great resource. Most, but not all, of the images above were taken from it and it contains many more, including quite a few reproductions of the scissors’ first appearances in art and print. If you are a design buff be on the lookout for it.

Hope you enjoyed.

-

Note: to the best of my knowledge the scissors pictured above are housed in the following Collections-

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Fairfield Museum in Bothwell, Ontario.

The Giuseppina Gioacchino Collection.

The Museum of Archeology in Konya Turkey.

The Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris.

The Anita Gatti Collection, Milan.

The GBZ Foundation for Paleontological Studies, Milan.