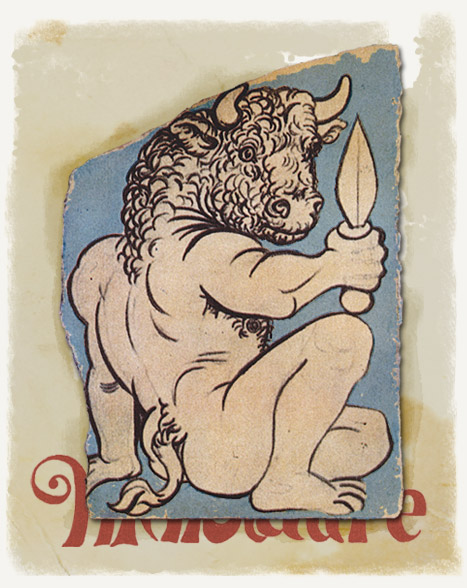

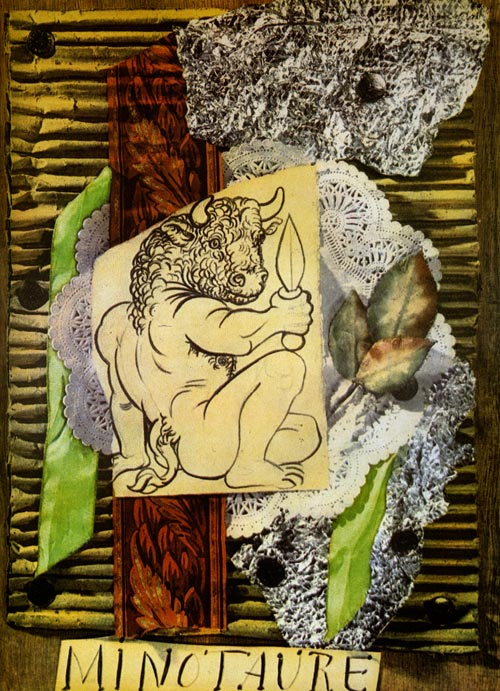

In 1933 Albert Skira, a young publisher of elegant art books, released the first two issues of a periodical which, though it would only last for 6 years, remains to this day one of the most impressive publications of its kind ever produced. It was called Minotaure and the reasons it is damned near legendary are simple– lavish production values of a quality unseen previously, and contributors who, from the editors to the essayists to the artists, went on to storm the hallowed annals of history.

Quote: “Filled with colour and black and white reproductions of a technical excellence unusual for the time, Minotaure first appeared in June 1933, and continued through thirteen issues, ceasing publication at the onset of World War II. The publishers set themselves the difficult task of bearing witness to the different movements in contemporary art, through text and image, demonstrating the interaction between the visual arts, literature, and science. Thus Minotaure documented the vast panorama of the 1930s, and served as a forum for encounters and discussions… Each number of Minotaure included contributions from artists, writers, philosophers, critics, psychoanalysts, and ethnologists, and was meant to be read as a collective work, many-voiced.”

Looking at it now, all these years later, with the canons of modernity firmly and irrevocably established in our minds, the list of contributors to Minotaure is almost comical: Breton, Picasso, Éluard, Miró, Chagall, Bataille, Magritte, Lacan, Matisse, Queneau, Duchamp, Man Ray, de Chirico, Dalí, Giacometti, Ernst, Rivera, Masson, Balthus, Matta, Bellmer, Arp, Brassaï, Huxley, Kandisnky, Jung… and these are just some names any average person is likely to recognize, add to it the archeologists, sinologists, anthropologists, ethnologists, numismatists, musicologists, historians, etc, etc, and the pedigree becomes overwhelming. One can easily imagine that even the snot-nosed kid who delivered baguettes and wine to the magazine’s offices went on to sell his dirty underpants at auction for a record breaking sum.

In any case, populist as the periodical form is, and impressive as this particular undertaking was, there seems no decent centralized source on the internet to look at Minotaure in greater detail. (At least not one that I could find with my English language searches, perhaps someone with more patience, or a command of French, can point us in the right direction.) As much as I would love to offer you excerpts from the poems and essays and criticisms and surrealist outbursts therein, alas, I can not. What I can offer you, however, are some pretty pictures.

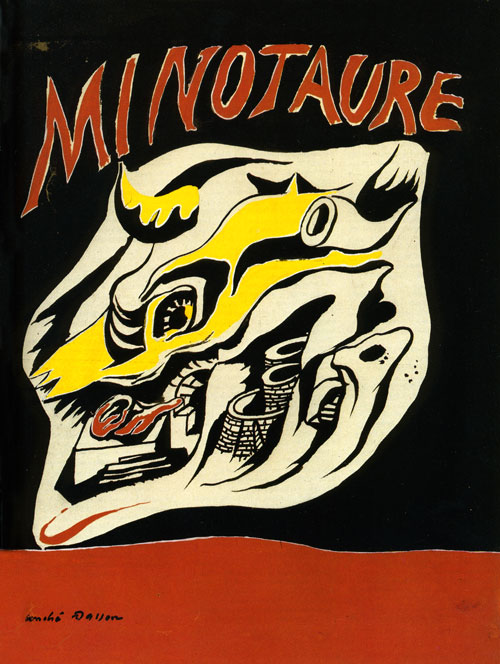

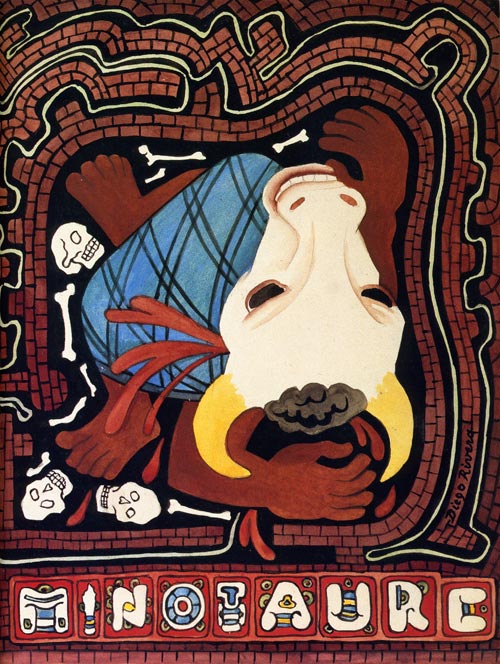

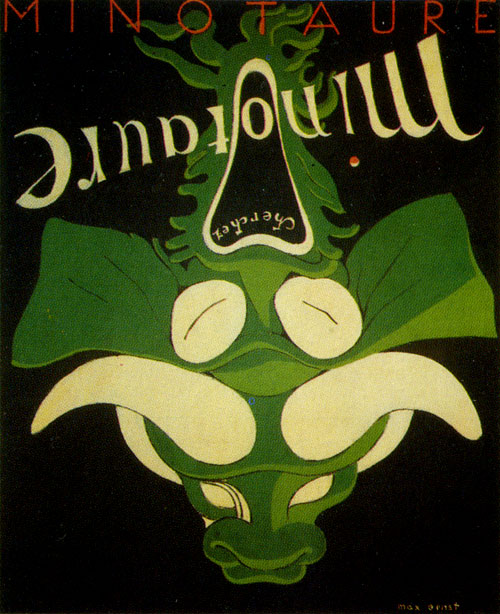

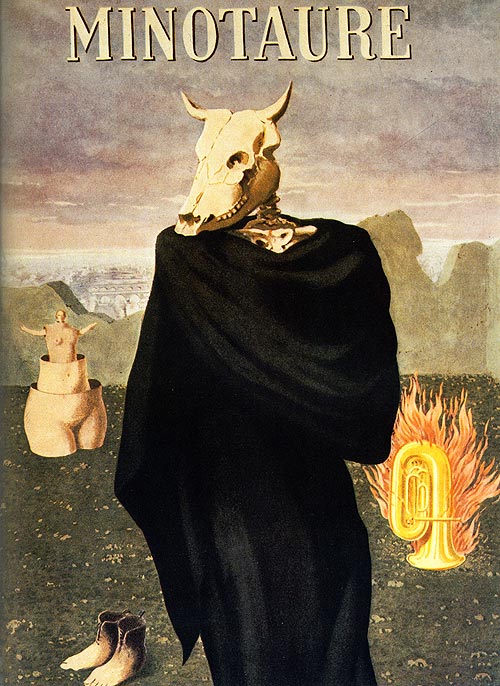

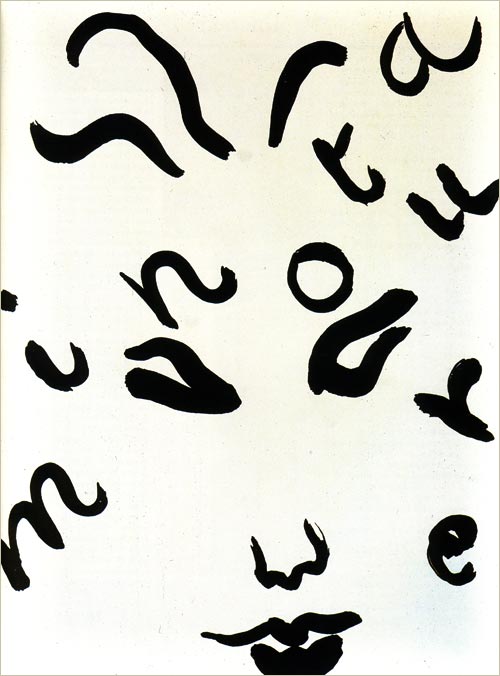

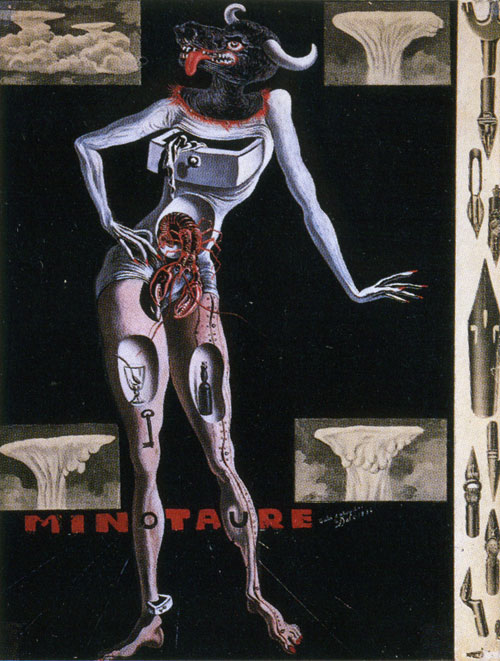

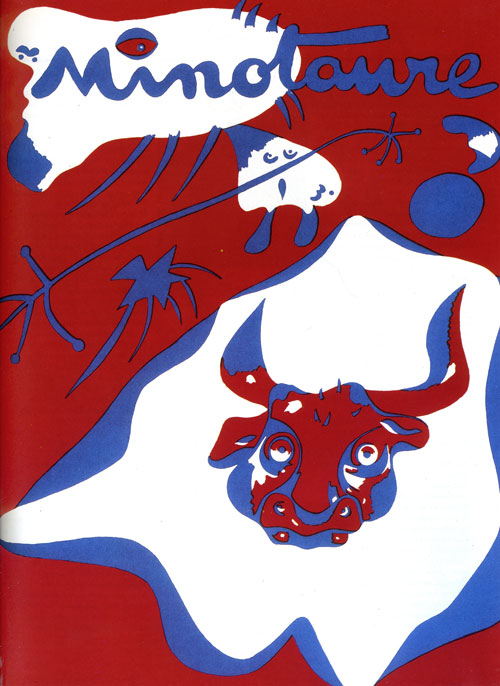

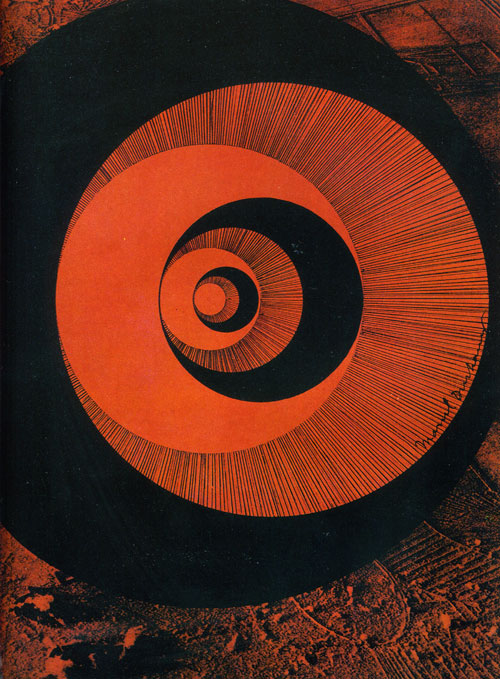

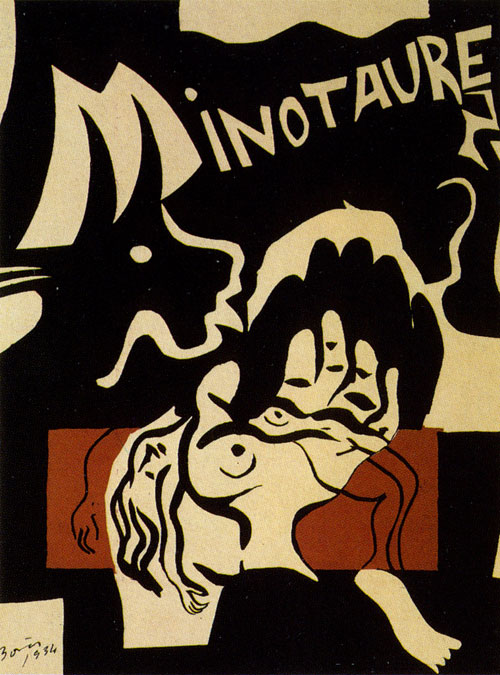

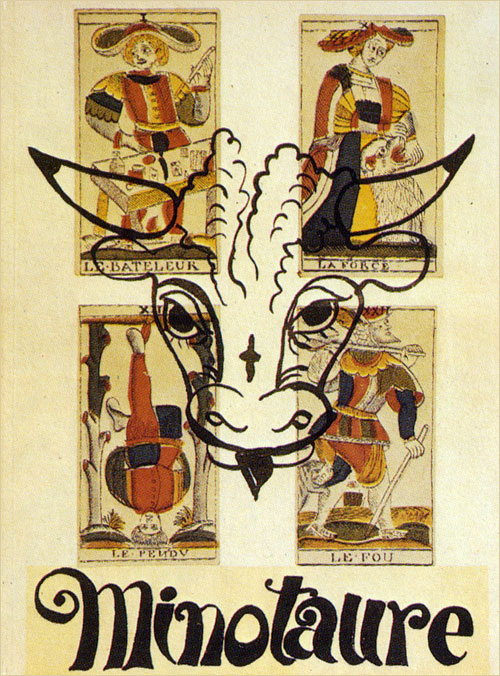

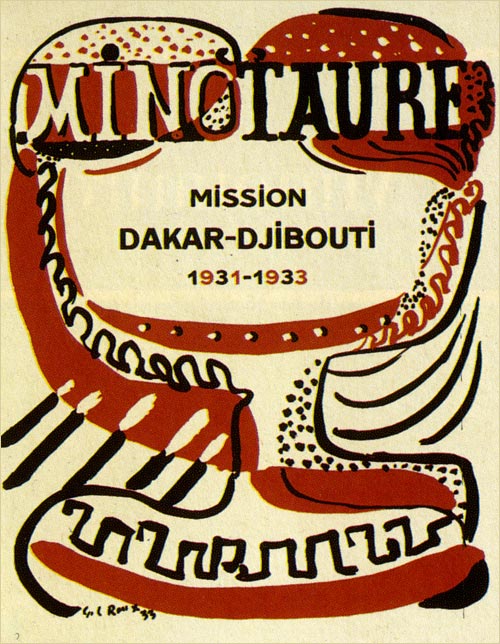

Below you will find decent-sized representations of each of Minotaure’s covers.

In closing I would just like to offer the following ten words to the many grandchildren and foundations and private owners and museums in whose collections and under whose copyright all of the material ever printed in Minotaure is held– “I’d buy a boxed set of reproductions in a second.” To which I’ll even add an eleventh word- “Please.”

For a bit more on the subject see here.

Hope you enjoyed.