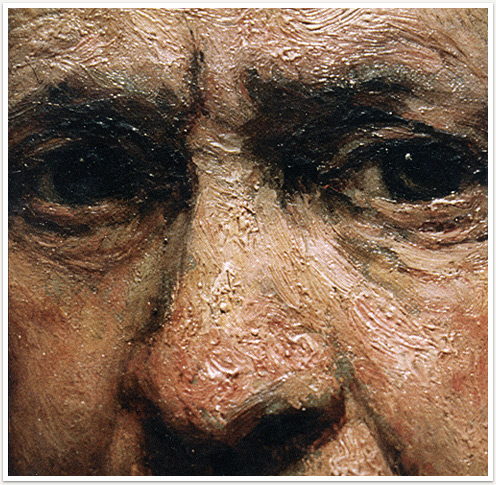

Today marks the 400th birthday of my homie Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. In celebration I offer a couple of paragraphs from a favorite book of mine, What Painting Is by James Elkins, which happens to touch on the physicality of Rembrandt’s canvas surfaces. See below.

From Chapter 4, How do substances occupy the mind?, in reference to the image which served as thumbnail to this post-

Rembrandt is well-known for the buttery dab of paint that he sometimes puts on the ends of the noses of his portraits, and this nose is certainly greasy and has its little spot of white. But touches like that do not stand alone: when Rembrandt was interested in what he was doing, as he was here, he coated entire faces in a glossy, shining mud-pack of viscid paint. The skin is damp with perspiration, as if he were painting himself in a hot room, and he slowly accumulated a slick sheen of sweat. It is impossible to ignore the strangeness of the paint. If I looked at my face in the mirror and saw this, I would be horrified. The texture is much rougher than skin, as if it is all scar tissue. As a painter works, the shanks of the brushes become repositories for dried paint, and flecks of that paint become dislodged and mix with fresh paint, rolling around on the canvas like sodden tumbleweeds. They are all over this face, forming little pimples or warts wherever they end up. (There is a large one halfway up the nose.) Among contemporary artists, Lucien Freud has made an entire technique out of these rolling flakes and balls, and he lets them congregate in his figures’ armpits and in their crotches. In short, the face is a wreck, much more disturbing than the unnaturally smooth faces that most painters prefer.

Although historians tend to see Rembrandt’s method as an attempt at naturalism, it goes much farther than portrait conventions have ever gone, then or since. Consider what is happening in the paint, aside from the fact that it is supposed to be skin. Paint is a viscous substance, already kin to sweat and fat, and here it represents itself: skin as paint or paint as skin, either way. It’s a self-portrait of the painter, but it is also a self-portrait of paint. The oils are out in force, like the uliginous oozing waters of a swamp bottom. The paint is oily, greasy, and waxy all at once—even though modem chemistry would say that is impossible. It sticks: it is tacky and viscid like flypaper. It has the pull and suction of pine sap. Over the far cheek, it spreads like the mucilage schoolchildren use to glue paper, resisting and rolling back. On the nose—it’s rude, but appropriate—the paint is semi-solid, as if the nose were smeared with phlegm or mucus. On the forehead, it looks curdled, like gelatin that is broken up with a spoon as it is about to set. There is drier paint around the eyes, and the bags under the eyes are inspissated hunks of paint, troweled over thin, greyish underpainting. The grey, which is left naked at the corner of the eye and in the folds between the bags, is the imprimatura, and the skin over it is heavy, thick, and clammy. The same technique served for the wings of the nose, where dribbles of paint come down to meet the nostril but stop short, leaving a gap where the grey shows through. Of course, the nostril is not a hole, but a plug of Burnt Sienna with Lamp Black, and it also lies on top of the grey imprimatura. Rembrandt’s thin moustache is painted with wiggles of buttery paint, almost like milk clinging to a real moustache. Over the eyes and eyelids there are thick strips of burned earth pigments -Lamp Black and Burnt Sienna— covering everything underneath. The tar spreads up and inward, and then falls into the hollows between the eyes and the nose in dense pools like duplicate pupils.

There is no limit to this kind of description, because Rembrandt’s paint covers the full range of organic substances. It is more fully paint, more completely an inventory of what can happen between water and stone, ⊕ than the other examples in this book. And that means it is also more directly expressive of qualities and properties: it is warm, greasy, oily, waxy, earthy, watery, inspissate. It is not dried rock, like Monet’s cathedral, nor water, like his marine paintings. The thoughts that crowd in on me when I look this paint have very little to do with the underlying triad, or with the named pigments or oils. They are thoughts about qualities: I feel viscid. My body is snared in the glues and emulsions, and I feel the pull of them on my thoughts. I want to wash my face.

-James Elkins.

“I want to wash my face.” Ha. Love it.