In 1929 a travelogue was released that would, through the chain reaction it set off, have a profound effect on American popular culture and by extension the American collective consciousness. It was written by a fellow with a questionable resume of personal traits said to include alcoholism, occultism, sensory deprivation, and sadism, who would ultimately commit suicide by pill-overdose. His is not a household name, and is rarely spoken, yet it is through the continued fascinated invocation of another name altogether that we unknowingly evoke his legacy: Zombie! Zombie!! Zombie!!!

He was William Buehler Seabrook, a reporter and Lost Generation writer (claiming the minor distinction of having written the first celebrity rehab tell-all) and it was his book, The Magic Island, a sensationalized account of his voodoo-mad travels throughout Haiti, that first ushered our beloved un-dead bugaboo, the zombie, onto American shores.

Though The Magic Island did

notrepresent the first usage in English print of the word zombie (it appeared as a term connected to a Voodoo snake god much earlier) as the author later claimed in his autobiography, Seabrook’s book was the first popular English language text to confront the phenomena of the Haitian “living dead” head-on. The book referred to these shambling, dead-eyed, unfortunates as “Zombies” + and they have moved, at varying speeds, among us ever since.

The popularity of his book, with its sensational but not altogether unsympathetic characterizations, dovetailed perfectly with a zeitgeist that would also yield the nearly concurrent release of Hollywood’s iconic monster features. The result of which was an immediate pop-cultural embrace, bringing this new terror into our stable of more veteran ghouls like Dracula and Frankenstein without so much as a second interview. Seabrook’s book was all it took.

The giddy excitement entertainers felt at having a new abomination to play with resulted, almost immediately, in a broadway play—Kenneth Webb’s 1932 flop Zombie—and a film—the infamous 1932 indie, and granddaddy of all zombie flicks, White Zombie—not to mention multiple lawsuits. A scant 3 years after America first saw the word in print courts were obliged to rule “zombies” as being in the public domain. And are they ever. After 1932 it is a truly rare thing for a year to pass by completely undisturbed by the walking dead.

Zombie! Zombie!! Zombie!!!

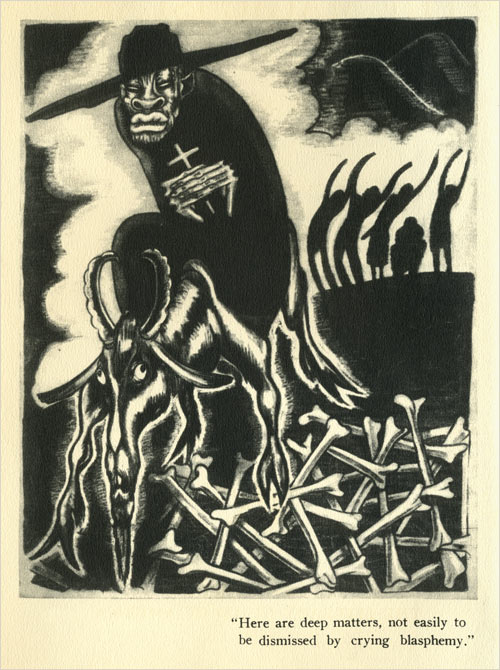

Though it is most notable for this popularization The Magic Island, a 336p book, in actuality only devoted 12 scant pages, a single chapter titled “...Dead Men Working in the Cane Fields” to le culte des morts’ handiwork. The rest of the book is full of sensational tales of ritual, magic, sacrifice, potions, feverish midnight sex-dances, and all of the objective reportage one might expect from an alcoholic, occult-dabbling, middle-aged white man traveling through Haiti in the 1920’s.

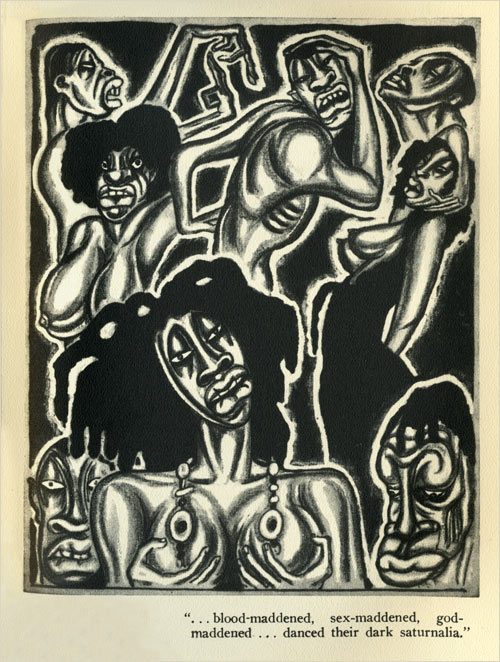

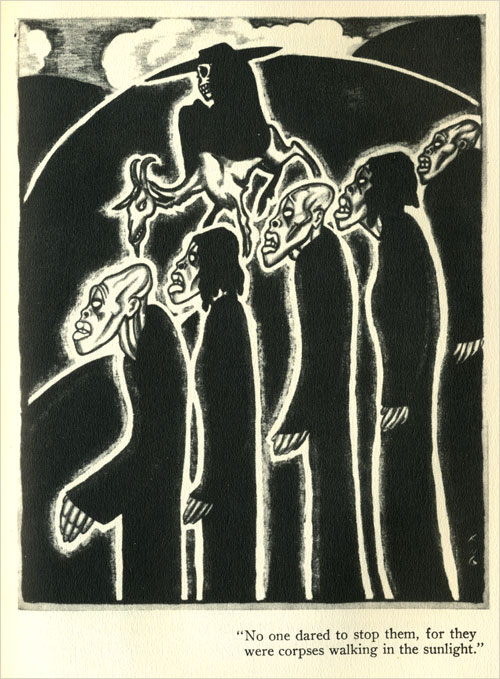

I picked up a first edition copy a few weeks back, just out of curiosity, and was thrilled to find that not only is it a pretty fascinating read, biases and euphemistic “of it’s time” pronouncements aside, but that their were pictures! Joy! The book contains about 30 photographs taken by Seabrook during his travels, but more interestingly a large group of original illustrations by a one Alexander King.

A search for more info on Mr. King does not offer much.

AskArt offers us this: “Described as a thief, morphine addict, failing playwright and painter, Alexander King was a man of iconoclastic observations and caustic humor who began his career as a painter of human figures, focused primarily on the face. Then he became an art thief, stealing fifty prints from the Metropolitan Museum. He was jailed twice, and married four times.”

While the IMDb says only: “Alexander King, by his own admission, had a very checkered career before becoming racontuer on residence during the Jack Parr years of “The Tonight Show”. A veteran newspaperman turned press agent, he published his various anecdotes in a series of off-beat books that were very popular at the time. Nearly forgotten today, King, who claimed to have been married five times, was a fixture on the TV talk show circuit from roughly the mid-1950s until his death in 1965.”

Various searches do reveal, without a doubt, that he illustrated many books throughout the 30’s and 40’s however, and with the pedigree outlined above, he was a perfect match for Seabrook and his Magic Island.

Below I’ve reproduced 9 of King’s illustrations from The magic Island including, for a few, some corresponding text by Seabrook. Have a look…

Quote: “Louis, son of Catherine Ozias of Orblanche, paternity unknown—and thus without a surname was he inscribed in the Haitian civil register—reminded me always of that proverb out of hell in which Blake said, “He whose face gives no light shall never become a star.” It was not because Louis’ black face, frequently perspiring, shone like patent leather; it glowed also with a mystic light that was not always heavenly. For Louis belonged to the chimeric company of saints, monsters, poets, and divine idiots. He used to get besotted drunk in a corner, and then would hold long converse with seraphim and demons, also from time to time with his dead grandmother who had been a sorceress.”

Quote: “The celebrants approached, processionally, singing, from the mystery house. At the head came the papaloi, an old man, blue-overalled, bare-footed, but with a surplice over his shoulders and a red turban on his head, waving before him the açon, a gourd-rattle wound round with snake-vertebrae. At his right and left, keeping pace with him, two young women held aloft, crossed above his head, two flags on which were serpentine and cabalistic symbols, sewn on with metallic, glittering beads. Behind him marched a young man bearing aloft, horizontally on his upstretched palms, a sword, and next the mamaloi, a woman in a scarlet robe and feathered headdress, who revolved as she progressed in a sort of dervish dance; next came marching, two and two, a chorus of twenty or more women robed in white, with white cloths wound bandana-wise on their heads, and as they slowly marched they chanted:

Damballa Oueddo,

Nous p’ vim

It would be best translated, I think, Oh, Serpent God, we come.”

Quote: “In the red light of torches which made the moon turn pale, leaping, screaming, writhing black bodies, blood-maddened, sex-maddened, god-maddened, drunken, whirled and danced their dark saturnalia, heads thrown weirdly back as if their necks were broken, white teeth and eyeballs gleaming, while couples seizing one another from time to time fled from the circle, as if pursued by furies, into the forest to share and slake their ecstasy.”

Quote: “One of the most dreaded forms of Haitian-African magic includes the dressing of a corpse in a garment of the person marked for vengeance and then exposing it to rot away in some secret place in the jungle. Men have gone stark mad seeking that jungle-hidden horror, and others have died hopelessly, searching. Fear, hunger, thirst, jungle-terror, one may say. Names again, tags, labels. But marked for death by the Voodoo curse, they died.”

Quote: “It seemed that while the zombie came from the grave, it was neither a ghost, nor yet a person who had been raised like Lazarus from the dead. The zombie, they say, is a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life—it is a dead body which is made to walk and act and move as if it were alive. People who have the power to do this go to a fresh grave, dig up the body before it has had time to rot, galvanize it into movement, and then make of it a servant or slave, occasionally for the commission of some crime, more often simply as a drudge around the habitation or the farm, setting it dull heavy tasks, and beating it like a dumb beast if it slackens.”

So while this text offers the first English language popularization of the word “zombie” those last 3 Illustrations, interestingly, represent the first images anyone associated the word. All in all fascinating bit of pop-cultural, if not exactly ethnographic or anthropological, history.

Jay A. Graybeal says in his terrific summation of Seabrook’s story: “Big lusty, restless, red-haired William Buehler Seabrook spent more than 20 years seeking fantastic adventure, then putting what he found into books which thrilled some, shocked many. But he never will write the story of his greatest adventure. Secretly and alone he embarked upon it not long ago by way of an overdose of sedative. The coroner says Bill Seabrook committed suicide. But his friends have a different explanation for what happened. They say he only was making another more drastic attempt to accomplish what he had tried, vainly, all his life to do—to get away from himself.”

Alester Crowley, an acquaintance of Seabrook’s, put it rather more bluntly in a diary entry: “The swine-dog W. B. Seabrook has killed himself at last.”

In 1966, a year after his death, a critic writing a review for a Seabrook biography said: “his principal literary contribution, it would seem, is the word zombie.” That may in fact be the truth. But how very impressive, built as it was on 12 short pages of reportage, that contribution turned out to be.

Zombie! Zombie!! Zombie!!!

Hope you enjoyed.

-

Related Linkage:

The Roots of the Modern Zombie Movie

Zombies in Popular Culture

Scifipedia: Zombies

The History of Zombies

Zombies in Early Horror Films

Voodoos and Obeahs

Gothic capitalism: The Horror of Accumulation and the Commodification of Humanity.

Black Religion and Black Magic: Prejudice and Projection in Images of African-derived Religions