In Russia, following a string of embarrassing defeats in the Russo-Japanese War and the infamous Bloody Sunday incident, during the period of the so called Failed Revolution, no less than 480 underground magazines sprung-up to voice the outrage of the many disparate groups and factions and movements—nihilists, anarchists, socialists, Mensheviks, Bolsheviks, etc—which though unorganized, were united in their calls for Tsarist reform. This outpouring of printed materials, critical of the State, was no small thing in a country with a long history of strict censorship and brutal punishments for dissension. These many short-lived publications are referred to, collectively, as “satires.”

Today, when we (soft, fattened, fiddling Nero’s in miniature that we are) think “satire” we reflexively brace ourselves for the haw-haws. We think of Colbert and the Onion, or if we’re a bit older maybe Weird Al and Doonesbury, or MAD magazine and Dr. Strangelove. If we’re real oldenhiemers, with half a mind left, we might conjure fond memories of The Great Dictator and H.L. Mencken and a childhood of Twain stories and Thomas Nast reprints. In any case, for us, “satire” may as well be a straight-up 1-to-1 synonym for “funny.”

These Russian satires? Not so much.

Granted, I can’t read Cyrillic, and the million little contextual and cultural cues on display are obviously totally beyond me; I’m literally just looking at pictures. But one gets the sense looking over these underground turn-of the-century publications that the “satire” was here accompanied by an entirely different sort of wink. The closest equivalent I can think of, which might resonate for those living in a free and democratic society, would be the evocation of “satire” as a defense in an ugly slander lawsuit… if slander were punishable by death. Not much “comedy” involved. In these Russian magazines “satire” would seem, more than anything, a thin but precious barrier against open reprisal.

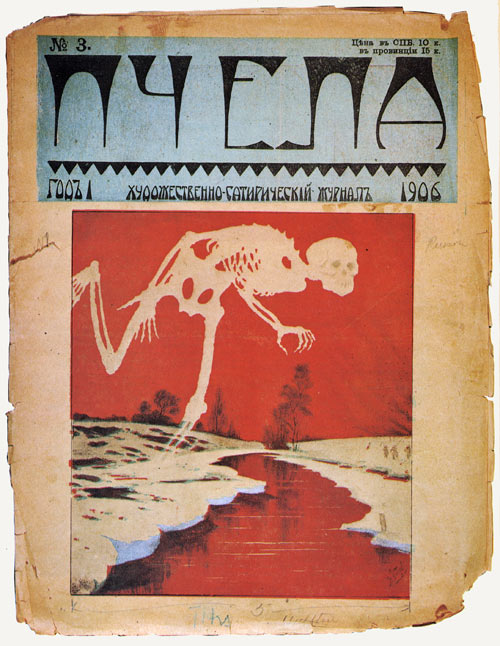

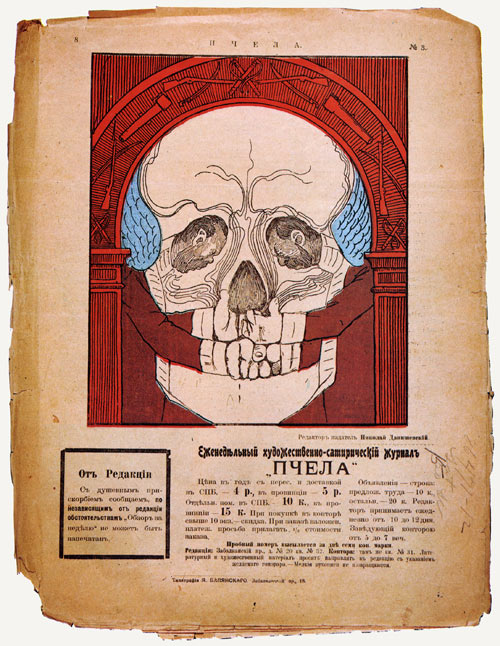

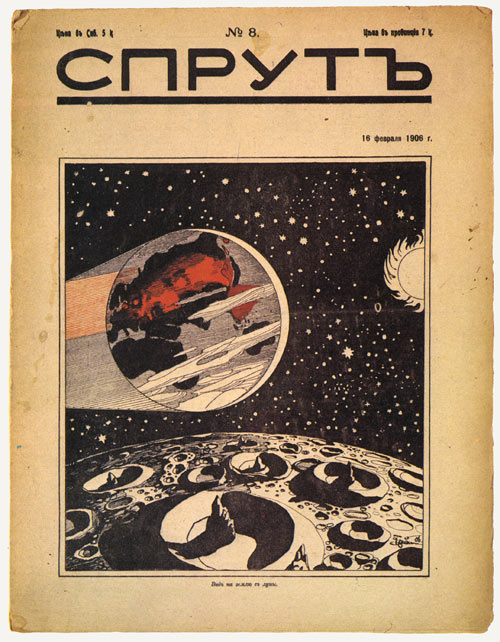

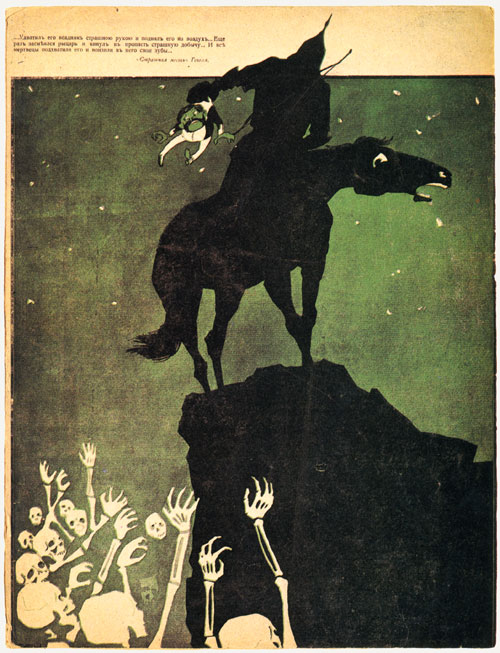

It’s said that these satires helped drive public opinion, to bring the criticisms which simmered just below the surface out into the open, and to force the first small concessions from the autocratic Tsar Nicolas II. Whether they in fact shamed the powers-that-be… it’s doubtful. I can say with certainty, however, that the graphic work in these publications, produced as they were under constant threat, does put most “underground” magazine work produced since to shame. The images, bleak and violent, mournful and angry though they are, remain powerful and terrifically beautiful.

Below, as illustration, I’ve reproduced a group of representative images culled from the book Blood & Laughter. Caricatures from the 1905 Revolution, by David King and Cathy Porter, put out in 1983.

Quote: “Bloody Sunday killed superstition, the old faith in a just Tsar, and unleashed a tumultuous rage among the masses… A huge wave of strikes swept the country, paralysing more than 100 towns and drawing in a million men and women. Throughout the summer peasants rioted while terrorists struck at figures of authority.

Alongside the struggle in street and factory was the struggle for the free press. Ministers and clerics suffered assassination more by the pen than the bullet as the revolution strove for the expression of powerful emotions long suppressed. A flood of satirical journals poured from the presses, honouring the dead and vilifying the mighty. Drawings of frenzied immediacy and extraordinary technical virtuosity were combined with prose and verse written in a popular underground language, veiled in allegory, metaphor and references to the past.”

“Russia had a rich history of satirical journalism. In the 1770s, in the reign of Katherine the Great, an elite of intellectuals close to the court developed a new ‘aesopian’ language — deeply subversive to the enlightened autocracy — to express their opposition to the old regime. The satire of the court flourished until the shadow of revolution in Europe drove the Empress to suppress it. Again in the 1860s highly popular satirical journals sprang up, drawing consciously on their courtly predecessors to curse the Crimean War and Tsar Alexander ll’s empty promises of reform. While populist revolutionaries went ‘to the people’ to make common cause with the peasants, radical journalists set out to collect folk-stories, popular sayings, soldiers’ songs and workers’ ballads. The old allegorical vocabulary was joined to the language of popular satire. By the 1870s these journals had been closed down, but this language was now part of everyday speech. Satirical writing returned to the underground, where it flourished, rooted in popular protest, until 1905. It was then that satire achieved its full power.”

“Satire turned holy names into household names, it insulted authority and withered reputations. Yet although the journals enjoyed an almost fanatical popularity, most writers clung to the anonymity of the underground where, apart from a few who became well-known after the Bolshevik revolution, they tended to remain. The artists proclaimed their names more openly, and a number of them — like Isaac Brodsky, Alexander Lyubimov, Nikolai Shestopalov, Pyotr Dobrynin and Boris Kustodiev — went on to become prominent soviet painters. They and many other artists had all been students in the master-class of the great realist painter llya Repin. In February 1905 Repin and his students had marched together in a demonstration against the Bloody Sunday massacre, and from then on they had all turned to paintings of street demonstrations, meetings and peasant uprisings.”

“For a few brief months the journals spoke with a great and unprecedented rage that neither arrest nor exile could silence. At first their approach was oblique, their allusions veiled, and they often fell victim to the censor’s pencil. But people had suffered censorship for too long.Satirists constantly expanded their territory and their targets of attack, demolishing one obstacle after another as they went, thriving on censorship. The workers’ movement grew in boldness, culminating in the birth of the St Petersburg Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, the people’s government. For fifty days the Tsar and his ministers were confronted by another power, another law. Journalists and printers seized the right to publish without submitting to the censor. The satirical journals then reached their apotheosis, until the revolution died as it had risen, bathed in blood.” -Cathy Porter, from her introduction to Blood & Laughter ,1983.

Well…

Apparently slaughter and hunger and class-struggle and brutal autocratic oppression aren’t very amusing when you get right down to it. On the other hand, perhaps for their intended audience these were amusing. Perhaps the simple but revolutionary act of speaking out against an oppressor was powerful enough to make even of a pile of human skulls feel exuberantly therapeutic. As a westerner, living a century later, totally removed from the language and culture and context I can’t rightly say. I mean, Russian humor has always had a slightly darker more grim cast than that of the West hasn’t it? Perhaps these “satires” offer a tiny clue as to why that might be.

If you’d like to see more of these Russian Satires the Yale University Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library has a very nice group of page scans, including interiors. Simply search for “Russia 1905.” Likewise, for more detailed information the Blood & Laughter. Caricatures from the 1905 Revolution is highly recommended.

Hope you enjoyed.